Okah Tubbee

By Sadie Van Vranken

Warner McCary, alias Okah Tubbee, was born in Natchez, Mississippi, around 1810. Listed as the child of a black woman owned by James McCary, Warner grew up in slavery. Warner became the property of his two older siblings upon McCary’s death in 1813. His autobiography describes his punishment at the hands of his mother, his rage at being called a “n-----,” and the many indignities of a childhood spent serving his older siblings. Although the exact date of his emancipation is unknown, Warner appears in 1843 as “a free man of Color of mulatto complexion.” By the mid-1840s, Warner began to travel as the Indian performer Okah Tubbee, claiming to be the son of Mushulatubbee, a well-known Choctaw chief. Although Warner’s parentage remains a mystery, it is unlikely that he was of Indian descent, and even less likely that he was the son of Mushulatubbee. Given that Warner began claiming Indian heritage after the age of thirty and was documented as the child of a black woman, his claim of Indian descent was more likely an escape from the indignity of slavery and blackness. Although Warner continued to claim Indian ancestry, he was hounded by skepticism and assumptions of his blackness for much of his life.

Laah Ceil Tubbee, Tubbee’s wife and the author of Tubbee’s narratives, was born Lucy Stanton. Lucy, a white woman, joined the early Mormonite movement in 1830 and came to feel a special call to help the Lamanites, the Mormon term for Native Americans. Early Mormon theology preached the conversion and redemption of the Lamanites and called for missionaries to convert Native Americans. Perhaps because of Lucy’s early interest in this work, when she met Okah Tubbee around 1845, she immediately accepted both his proposal of marriage and his Indianness. Whether she privately doubted Tubbee’s native identity or knew it to be a misdirection, within a few years Lucy also began to claim a Native American identity, using the name Laah Ceil Tubbee and claiming at times Mohawk, and at times Delaware, ancestry. Despite the clear trail linking Laah Ceil to the white Lucy Stanton, scholarship on the Tubbees has, until extremely recently, accepted Laah Ceil’s claim to Indian heritage, even as it questioned Okah Tubbee’s. Equally, contemporary scholarship has often failed to examine the couple’s time as part of the Mormon community and the controversy stirred by their marriage.

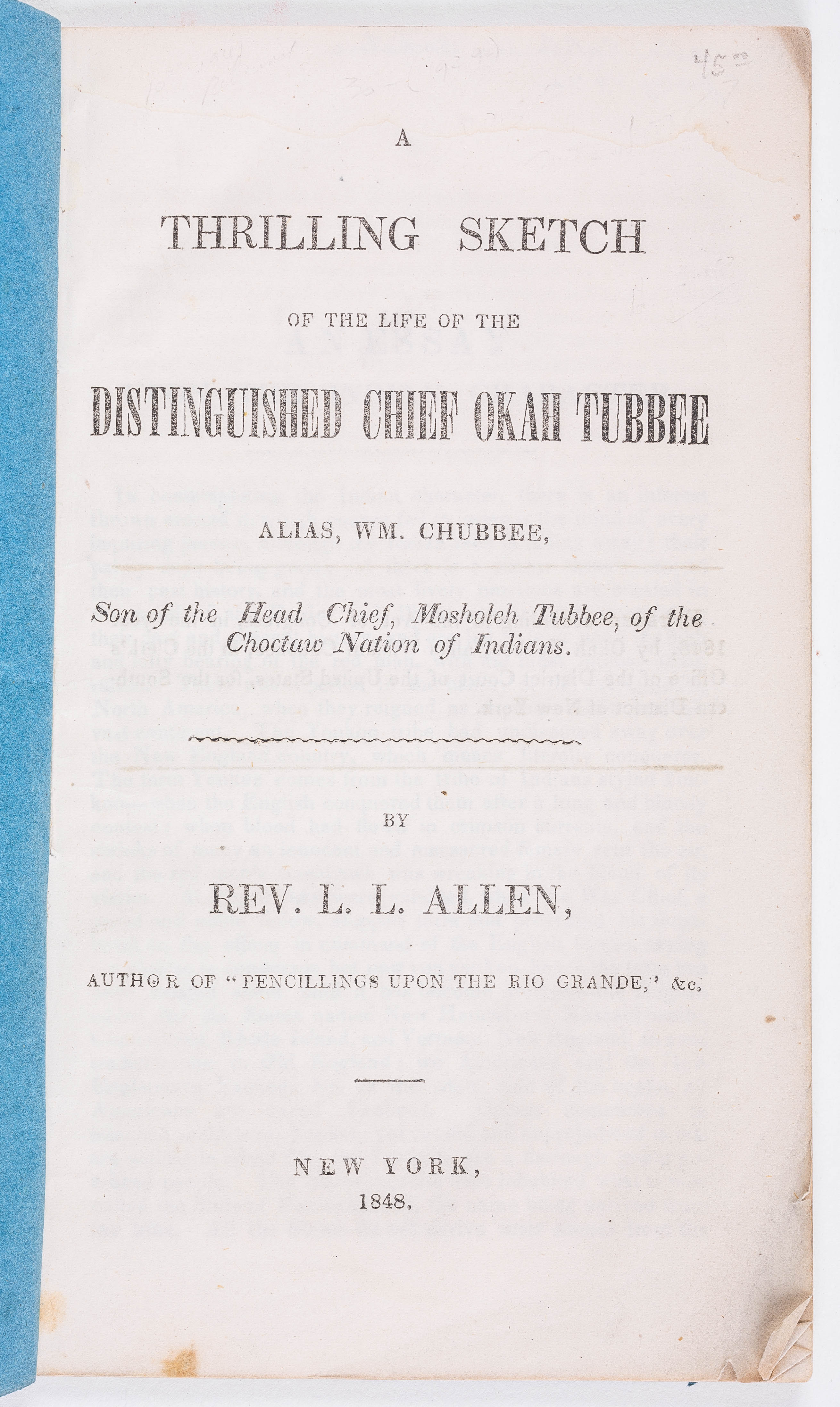

Tubbee’s narrative, published twice in 1848 and once in 1852, draws upon popular imaginations of native culture and temperament to boost McCary’s claim to Indianness. Undoubtedly used to accompany Tubbee’s stage performances, the narrative reimagines his life as that of a noble Indian. The first version of his narrative, A Thrilling Sketch of the Life of the Distinguished Chief Okah Tubbee Alias, Wm. Chubbee, Son of the Head Chief, Mosholeh Tubbee, of the Choctaw Nation of Indians, was likely published by Lewis Leonidas Allen, although Tubbee is listed as the copyright holder. Allen, who served as the Tubbees' agent in 1848, compiled the narrative through letters from Laah Ceil Tubbee. The narrative opens with a romanticized depiction of the American Indian, casting native culture as a disappearing, charming curiosity. After a description of a covenant between the Choctaws and the six nations, Tubbee’s narrative begins. Focused on describing his early life, the narrative follows his quest to discover his native ancestry. The narrative ends by promising “this thrilling and deeply interesting sketch will be continued in forthcoming numbers, and presented to the public in a neat and interesting form from Cameron’s Steam Power Presses.”

When the narrative next appeared in print, however, it was not from Cameron’s Steam Power Presses, but rather printed by H.S. Taylor in Springfield, Massachusetts. This narrative, stated as printed “for Okah Tubbee,” retains Allen’s editorial essay, but contains a greater emphasis on Tubbee’s claim to Indian heritage. With Laah Ceil listed as the author, this version and subsequent editions emphasize the Tubbees' role in preparing, publishing, and promoting the narrative, removing any mention of Allen. The 1852 edition, printed in Toronto, redirects the narrative’s focus toward Tubbee’s claim to medicinal expertise and aims to enhance his reputation as an Indian doctor.

The inclusion of Tubbee’s narratives on this list of black self-published texts underscores the fluidity of racial identification and the perils of identifying the “black author.” Whether Tubbee was truly, as he claimed, an Indian stolen into slavery at infancy, he battled with the public construction of his race throughout his life. As newspapers battled over Tubbee’s identity and the visible indicators of race, Tubbee’s narrative worked to counteract claims of his blackness, remolding public perception of his body into the popular perception of Indianness. Likewise, Laah Ceil’s invented Indian identity and the scholarly acceptance of her claim to Indianness demonstrates the privileging of “white Indian” over “black Indian” in the historical and contemporary imagination, offering a fascinating juxtaposition of the success of Laah Ceil and Okah Tubbee in their quest to reinvent themselves as Indians.

Further Reading:

Documenting the American South on Okah Tubbee: https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/tubbee1848/summary.html.

Hudson, Angela Pulley. Real Native Genius: How an Ex-Slave and a White Mormon Became Famous Indians. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Littlefield, Daniel F., Jr., ed. The Life of Okah Tubbee. Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 1988.