The Confessions of Nat Turner

Local Southampton attorney Thomas Ruffin Gray asked for and was granted permission to interview Nat Turner while he awaited trial in the Southampton courthouse. Gray opens his prefatory remarks with the observation that the Turner rebellion has “greatly excited the public mind,” and by interviewing Turner, he hopes to correct these misimpressions. “Every thing connected with this sad affair was wrapt in mystery,” writes Gray, and historians have debated how successful Gray was in unwrapping this mystery (see Allmendinger, Breen, and Tomlins for opposing views). Despite Gray’s considerable efforts throughout Confessions to show its veracity, many have debated how “faithful” this confession was: did Turner actually use these words? And if so, how free was he to speak? Gray first went to Richmond to print the pamphlet, but having no luck, he then went to Washington, D.C., to secure the copyright. Kenneth Greenberg reports that the edition of fifty thousand copies, priced at 25 cents each, was published in Baltimore on November 22, 1831 (1996; 8).

The Authentic and Impartial Narrative had already been published when Confessions came out, but Gray had been an eyewitness to some of the events and to the subsequent trial. Gray had been part of the militia that organized the first morning of the rebellion, and he served as counsel for four defendants’ trials prior to Turner’s. Gray depicts Turner as a religious leader who at a young age was touched by divine greatness, and whose mother concluded that “surely” he would “be a prophet.” According to Confessions, a divine spirit also dictated Turner’s otherwise unexplainable return after running away in 1825. Turner’s religiosity is not dismissed as a ruse: “He is a complete fanatic, or plays his part most admirably.” Turner’s youth was also marked by an intelligence that sets him apart from others, and in this sense, Gray portrays him as a victim. Slavery had “warped and perverted” his mind, Gray writes.

Unlike the Authentic and Impartial Narrative, Gray promises restraint as he “will not shock the feelings of humanity, nor wound afresh the bosoms of the disconsolate sufferers…by detailing the deeds of their fiend-like barbarity,” and yet, Turner is still portrayed as evoking considerable fear in Gray. Gray remarks, “I looked on him and my blood curdled in my veins.” Confessions makes clear that Turner was very much the leader of the group of rebels and offers vivid details of the killings, explaining that Turner was not able to kill because his “sword was dull.” He is the one who gave orders to “halt and form” when the eighteen white men approached at Parker’s farm. Compared to the Authentic and Impartial Narrative, the tone here is calm, though the confession does not spare some details that depict Turner as a monster: “We found no more victims to satisfy our thirst for blood.”

The entire text and XML/TEI source are available at Documenting the American South.

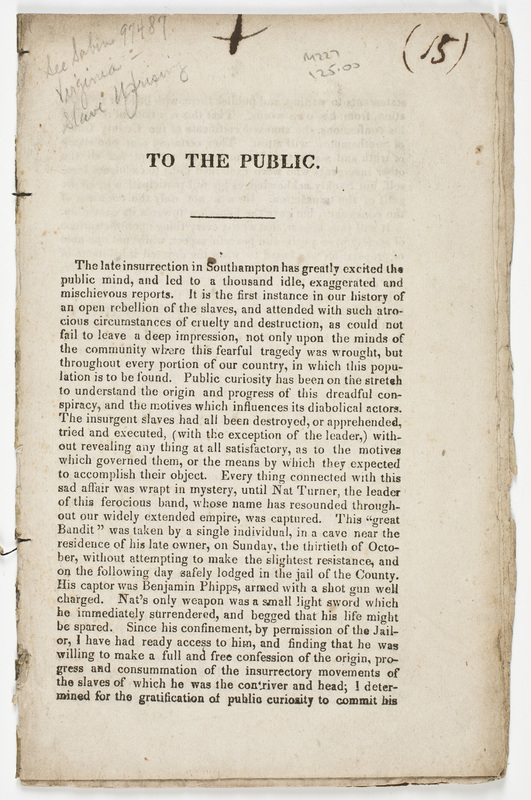

Thomas Gray and Nat Turner, The Confessions of Nat Turner. From the collection of the American Antiquarian Society.