Catalog

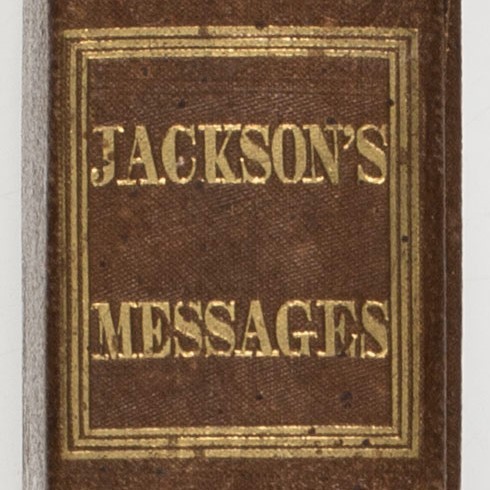

Click here to find out why AAS keep seven copies of the same edition of The Messages of Gen. Andrew Jackson.

If a book lands in a library but no one knows it is there, does it matter if it exists?

Such is the existential crisis faced with every new collection item added to the AAS library. The complications involved in making a newly acquired book visible are only compounded when it arrives as part of a mass of hundreds of volumes such as the William C. Cook Jacksonian Era Collection.

How do we expose the treasures of AAS collections to the world? The short answer is cataloging. The difficulty is that few of us understand exactly what cataloging is, let alone the work it entails and how it functions to support scholarship. Scarcer still are the donors who are willing to pay for this essential scholarly service—and good cataloging really is scholarship. Fortunately, in the case of the William C. Cook Jacksonian Era Collection, Mr. Cook wisely gave funding to support the cataloging of the collection to encourage its use. All of the titles in the William C. Cook Jacksonian Era Collection have catalog records in the AAS online catalog.

Anatomy 101 for Catalog Records

The good news is every collection item that comes through the American Antiquarian Society’s door now gets at least a brief online catalog record as part of the acquisitions process. AAS catalog records are freely accessible from anywhere online, as this is the way researchers are able to locate collection materials they might need.

The not-quite-so-good news is that these cataloging records can be incredibly complex and often require deep bibliographic knowledge to fully understand. The Society’s blog, Past is Present, had a fun blog post by a former AAS staff member, Diann Benti, that playfully introduced the uninitiated to some of the basic details of a typical catalog record with commentary on how the various elements are derived.

Click on the illustration of the catalog record to expand it and read the commentary, or click here to read the entire blog post from Past is Present.

Click on the illustration of the catalog record to expand it and read the commentary, or click here to read the entire blog post from Past is Present. Most people will never need to know all those details about the Library of Congress’s subject headings or AAS’s call number classification system, but when evaluating cataloging records it can help to know a little bit about how they are created.

Editions, Impressions, Issues, States, & Copies

To understand how catalog records are created, it is best to start with how the books themselves were created. The Society's head of cataloging, Alan Deguitis, explains in his own words how AAS catalogers determine when to create a new catalog record:

"When describing a copy of a monographic work (newspapers, periodicals, scores, visual materials, and manuscripts are another matter for another day), an AAS cataloger creates a separate online catalog record for each identifiable edition, impression, and issue of the work. (An edition may be defined as all copies printed from a given setting of type; an impression as all copies of an edition printed at any one time; and an issue as a group of copies within an impression which constitute an intentionally planned publishing unit.) Variant states within an issue (which usually reflect the correction of errors rather than the intent to create a separate group of copies) are described in a single record. The Society often has multiple copies of a single work. The copies may reflect the existence of multiple editions, multiple impressions of an edition, multiple issues of an impression, and/or variant states of an issue. Additionally, the Society may keep multiple copies that are bibliographically identical because the copies may have different marks of provenance that are themselves of interest."

North American Imprints Program

Such complex details are bread and butter for AAS catalogers. Careful examination and comparison of individual copies is the type of labor-intensive and value-added work for which AAS is renowned. In the past, such a detailed approach was applied most often to incunabula (the earliest printing before 1501) or to famous authors’ first editions, where various “issue points” can mean the difference of tens of thousands of dollars on the rare book market. The Bibliography of American Literature (known as the BAL), for example, takes such a comprehensive bibliographical approach to the works of American authors.

Through the North American Imprints Program (NAIP), AAS’s crack team of rare book catalogers are applying this type of intensive focus to all of the earliest North American imprints, including copy specific information about the Society’s holdings. In an ideal world, AAS would want to treat every item in its collections to this level of detailed analysis. In the real world, AAS catalogers have applied this detailed level of rare book cataloging to all known copies of U.S. imprints before 1801, and are completing work on the decades from 1801 to 1840. The publications from the early nineteenth century are taking longer because of what has been described as an explosion in print culture in the Jacksonian Era in particular, thanks to innovations such as mechanical presses, machine-made paper, and stereotyping technologies. All of the pre-1840 imprints from the William C. Cook Jacksonian Era Collection have received or will receive this incredibly detailed level of cataloging.

Why Keep a Second (or Third) Copy?

Given the Society’s goals for NAIP rare book cataloging, the additional information provided by multiple copies can add valuable insight into the book’s publication history. A catalog record is intended to describe the ideal copy of a publication. Yet, by necessity, records are (almost) always created using evidence supplied from the one particular instance of that publication—the one that happens to be in the cataloger’s hand at that time. That example might be misbound or rebound or missing pages. Even if the copy in hand is not defective, examining it in isolation gives no clue that there may have been a wide variety of issues and states produced as part of this one edition. Making one copy stand in for an entire edition can distort the bibliographic record, but there is no way to know if that is the case without examining multiple copies of a publication.

Additional copies may represent a later printing or reissue (i.e., a book might be offered for sale later in time than its title page would suggest, possibly evinced by a later date on booksellers’ advertisements bound in after the main text). They may also document stop-press corrections (i.e., when a print run was interrupted to fix an error discovered after some sheets had already been through the press). An additional copy may be kept for its original binding. Even if damaged, such bindings can provide useful evidence regarding whether the publisher issued it in an edition binding or perhaps indicating the speed of production or the inexperience (or inexpensiveness) of the labor.

How many copies are too many, though? In just one example from the William C. Cook Jacksonian Era Collection with many possible variants, the power of exponential math means that the 1837 edition of Jackson’s Messages could theoretically have had up to thirty-six different permutations! In this case AAS has just seven examples, but how does one represent such bibliographical complexity in the online catalog? At the most basic level, are we talking about one catalog record? Three? Seven? The answer may surprise you. (See the example in the sidebar.)